Immanuel Velikovsky – The Bonds Of The Past

Velikovsky at Princeton

Immanuel Velikovsky bestseller Worlds in Collision

The audacity to think freely vs the inability of those without vision

Immanuel Velikovsky – Challenging Truths (Camera Three – 1964)

Immanuel Velikovsky – a Documentary

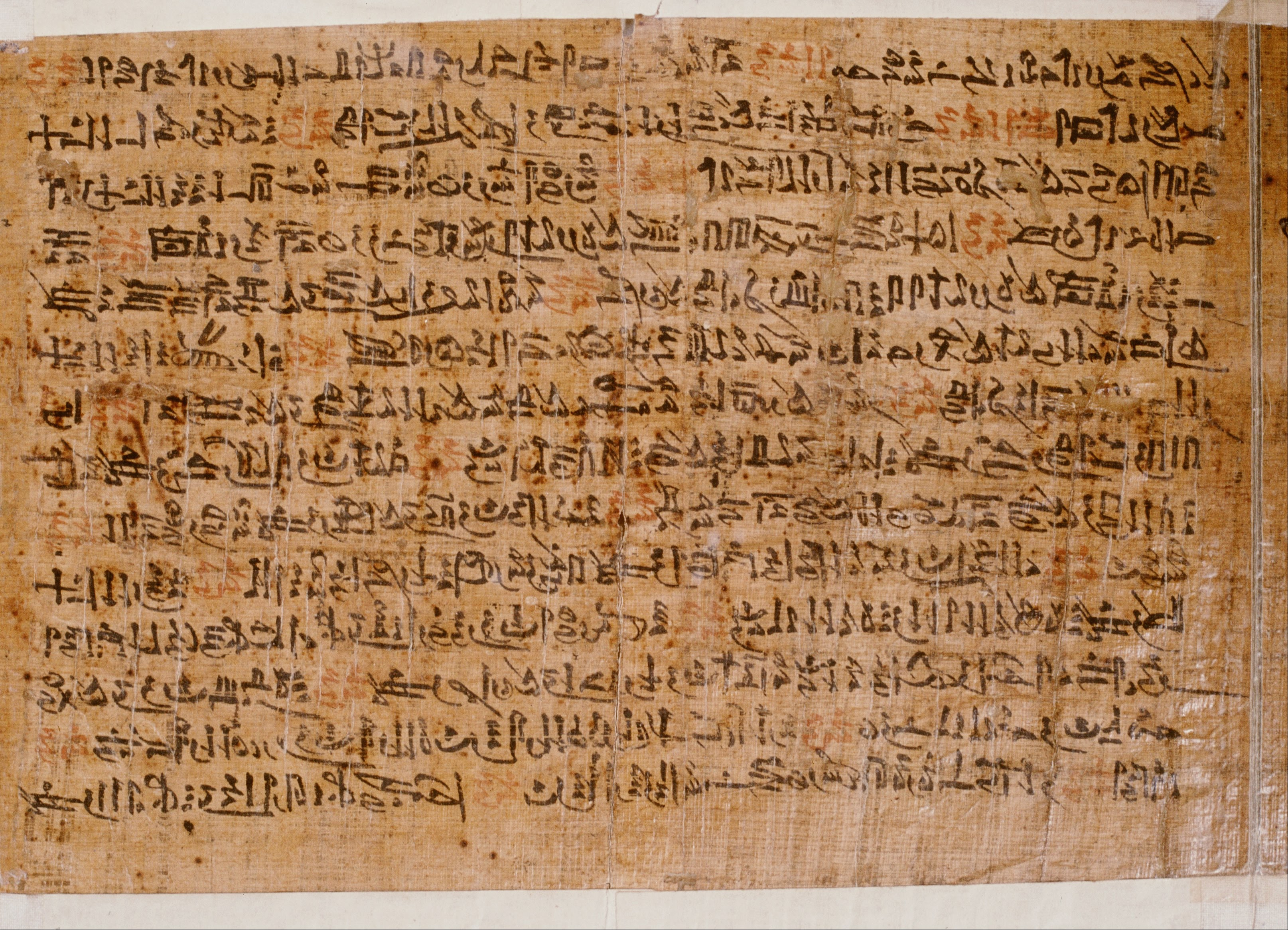

The Papyrus Ipuwer

Translate

Translate The Papyrus Ipuwer

The Papyrus Ipuwer

Excerpt from Ages in Chaos, by Immanuel Velikovsky:

“It is not known under what circumstances the papyrus containing the words of Ipuwer was found. According to its first possessor (Anastasi), it was found in “Memphis”, by which is probably meant the neighborhood of the pyramids of Saqqara. In 1828 the papyrus was acquired by the Museum of Leiden or Rijksmuseum van Oudheden in the Netherlands and is listed in the catalogue as Leiden 344.

The papyrus is written on both sides. The face (recto) and the back (verso) are differentiated by the direction of the fiber tissues; the story of Ipuwer is written on the face, on the back is a hymn to a deity. A facsimile copy of both texts was published by the authorities of the museum together with other Egyptian documents. The text of Ipuwer is now bolded into a book of seventeen pages, most of them containing fourteen lines of hieratic signs (a flowing writing used by the scribes, quite different from pictorial hieroglyphics). Of the first page only a third — the left or last part of eleven lines — is preserved; pages 9 to 16 are in veery bad condition — there are but a few lines at the top and bottom of the pages — and of the seventeenth page only the beginning of the first two lines remains.

In 1909 the text, translated anew, was published by Alan H. Gardiner under the title, The Admonitions of an Egyptian Sage from a Hieratic Papyrus in Leiden. Gardiner argued that all the internal evidence of the text points to the historical character of the situation. Egypt was in distress; the social system had become disorganized; violence filled the land. Invaders preyed upon the defenceless population; the rich were stripped of everything and slept in the open, and the poor took their possessions. “It is no merely local distrubance that is here described, but a great and overwhelming national disaster.”

Hieratic (Greek ἱερατικά hieratika; literally “priestly”) is a cursive writing system used in the provenance of the pharaohs in Egypt and Nubia. It developed alongside cursive hieroglyphs,[1] from which it is separate[dubious ] yet intimately related. It was primarily written in ink with a reed brush on papyrus, allowing scribes to write quickly without resorting to the time-consuming hieroglyphs.

In the Proto-Dynastic Period of Egypt, hieratic first appeared and developed alongside the more formal hieroglyphic script. It is an error to view hieratic as a derivative of hieroglyphic writing. Indeed, the earliest texts from Egypt are produced with ink and brush, with no indication their signs are descendants of hieroglyphs. True monumental hieroglyphs carved in stone did not appear until the 1st Dynasty, well after hieratic had been established as a scribal practice. The two writing systems, therefore, are related, parallel developments, rather than a single linear one.[1]

Hieratic was used throughout the pharaonic period and into the Graeco-Roman Period. Around 660 BC, the Demotic script (and later Greek) replaced hieratic in most secular writing, but hieratic continued to be used by the priestly class for several more centuries, at least into the 3rd century AD.

Hieratic script (unlike cursive hieroglyphs)[dubious ] always reads from right to left. Initially, hieratic could be written in either columns or horizontal lines, but after the 12th Dynasty (specifically during the reign of Amenemhat III), horizontal writing became the standard.

|

February 1974 from TheImmanuelVelikovskyArchive Website

In my published books, notwithstanding often repeated allegations, no physical law is ever abrogated or “temporarily suspended”; what I offered in them is primarily a reconstruction of events from the historical past. Thus I did not set out to confront the existing views with a theory or hypothesis and to develop it into a competing system.

My work is first a reconstruction, not a theory; it is built upon studying the human testimony as preserved in the heritage of all ancient civilizations – all of them in texts bequeathed beginning with the time man learned to write, tell in various forms the very same narrative that the trained eye of a psychoanalyst could not but recognize as so many variants of the same theme. In hymns, in prayers, in historical texts, in philosophical discourses, in records of astronomical observations, but also in legend and religious myth, the ancients desperately tried to convey to their descendants, ourselves included, the record of events that took place in circumstances that left a strong imprint on the witnesses.

There were physical upheavals on a global scale in historical times; the grandiosity of the events inspired awe.

From the Far East to the Far West – the Japanese, Chinese and Hindu civilizations; the Iranian, Sumerian, Assyrian, Babylonian, Hitto-Chaldean, Israelite and Egyptian records; the Etruscan, Attic and Roman theogonies and philosophies; Scandinavian and Icelandic epics; Mayan, Toltec and Olmec art and legends – all, with no exception, were dominated by the knowledge of events and circumstances that only the most brazen attitude of science could so completely disregard. The scientific community starts its annals with Newton, paying some homage to Copernicus, Kepler and Galileo, unaware that the great ones of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries searched through classical authors of antiquity for their great discoveries.

Then why does modern science disregard the persistent reports of events witnessed and recorded in many languages in the writings of the ancients and also transmitted from generation to generation by communities unable to write, by American Indians, by the people of Lapland, the Voguls of Siberia, the aborigines of tropical Africa, the Tahitians in the South Pacific?

Vitebsk

The ancient city of Vitebsk strides the Western Dvina. This large stream rises in the Valdai Hills, in that watershed from which also the Volga flows east, and the Dneper south. Not far from Vitebsk the Dvina makes a bend and majestically continues to the northwest. It empties its water into the Baltic Sea in the Gulf of Riga. In Tzarist times it used to carry barges and steamboats with the produce of the region to Riga and from there to the overseas markets. Vitebsk was the capital of the Vitebsk Gubernia, one of the districts into which Tzarist Russia was divided. The town had about sixty or seventy thousand people, a substantial part of them being Jews: Vitebsk was in the “pale”—or inside the “line of permitted settlement.” It was not famous for its learning like a few smaller localities in Western Russia, renowned for their yeshivot or for the great authorities in Jewish studies residing in them and thus attracting the needle of the intellectual compass. But neither was Vitebsk among the cities in the “pale” which acquired an unsavory reputation. Not far away was the town of Liubavitchi, the seat of the famous dynasty of Hassidic zadiks (righteous men). Yet I believe the Jewry of Vitebsk was not Hassidic in the main. Its people were plain and kind, of a pleasant disposition, a little given to dreams and melodies. This quality is shown in the compositions of Marc Chagall, born in Vitebsk, who even in his old age, long away from his birthplace, continued to depict in many of his paintings Vitebsk and its Jews. Chagall and I never met, unless I chanced to come across him, a lad seven years older than myself, in the time we both resided in that city; but I left it much earlier than he, at the age of six and a half, never to visit it again; yet I could fill many pages with my memories of Vitebsk. Read More – part of Velikovsky Autobiography Worlds in Collision

Worlds in Collision Immanuel Velikovsky Part 2 – |