National Geographic – Big and Bigger

Reinventing The Hoover Dam | Megastructures – National Geographic documentary click here

Boulder, Colorado Flooding: Dams Breached, Thousands Evacuate

Remove the Dams to Save the Salmon?

Dams and River Ecology

After Largest Dam Removal in U.S. History, This River Is Thriving

SundayReview | Opinion

Large Dams Just Aren’t Worth the Cost

By JACQUES LESLIE AUG. 22, 2014

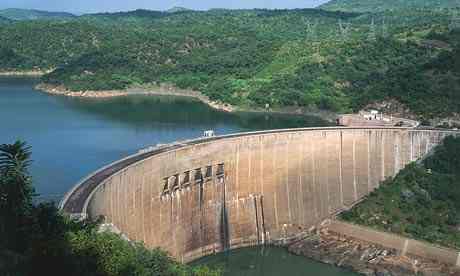

An aerial view of the Kariba Dam between Zambia and Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe, circa 1965. Credit Paul Popper/Popperfoto — Getty Images

THAYER SCUDDER, the world’s leading authority on the impact of dams on poor people, has changed his mind about dams.

A frequent consultant on large dam projects, Mr. Scudder held out hope through most of his 58-year career that the poverty relief delivered by a properly constructed and managed dam would outweigh the social and environmental damage it caused. Now, at age 84, he has concluded that large dams not only aren’t worth their cost, but that many currently under construction “will have disastrous environmental and socio-economic consequences,” as he wrote in a recent email.

Mr. Scudder, an emeritus anthropology professor at the California Institute of Technology, describes his disillusionment with dams as gradual. He was a dam proponent when he began his first research project in 1956, documenting the impact of forced resettlement on 57,000 Tonga people in the Gwembe Valley of present-day Zambia and Zimbabwe. Construction of the Kariba Dam, which relied on what was then the largest loan in the World Bank’s history, required the Tonga to move from their ancestral homes along the Zambezi River to infertile land downstream. Mr. Scudder has been tracking their disintegration ever since.

Once cohesive and self-sufficient, the Tonga are troubled by intermittent hunger, rampant alcoholism and astronomical unemployment. Desperate for income, some have resorted to illegal drug cultivation and smuggling, elephant poaching, pimping and prostitution. Villagers still lack electricity.

Mr. Scudder’s most recent stint as a consultant, on the Nam Theun 2 Dam in Laos, delivered his final disappointment. He and two fellow advisers supported the project because it required the dam’s funders to carry out programs that would leave people displaced by the dam in better shape than before the project started. But the dam was finished in 2010, and the programs’ goals remain unmet. Meanwhile, the dam’s three owners are considering turning over all responsibilities to the Laotian government — “too soon,” Mr. Scudder said in an interview. “The government wants to build 60 dams over the next 20 or 30 years, and at the moment it doesn’t have the capacity to deal with environmental and social impacts for any single one of them.

“Nam Theun 2 confirmed my longstanding suspicion that the task of building a large dam is just too complex and too damaging to priceless natural resources,” he said. He now thinks his most significant accomplishment was not improving a dam, but stopping one: He led a 1992 study that helped prevent construction of a dam that would have harmed Botswana’s Okavango Delta, one of the world’s last great wetlands.

Part of what moved Mr. Scudder to go public with his revised assessment was the corroboration he found in a stunning Oxford University study published in March in Energy Policy. The study, by Atif Ansar, Bent Flyvbjerg, Alexander Budzier and Daniel Lunn, draws upon cost statistics for 245 large dams built between 1934 and 2007. Without even taking into account social and environmental impacts, which are almost invariably negative and frequently vast, the study finds that “the actual construction costs of large dams are too high to yield a positive return.”

The study’s authors — three management scholars and a statistician — say planners are systematically biased toward excessive optimism, which dam promoters exploit with deception or blatant corruption. The study finds that actual dam expenses on average were nearly double pre-building estimates, and several times greater than overruns of other kinds of infrastructure construction, including roads, railroads, bridges and tunnels. On average, dam construction took 8.6 years, 44 percent longer than predicted — so much time, the authors say, that large dams are “ineffective in resolving urgent energy crises.”

DAMS typically consume large chunks of developing countries’ financial resources, as dam planners underestimate the impact of inflation and currency depreciation. Many of the funds that support large dams arrive as loans to the host countries, and must eventually be paid off in hard currency. But most dam revenue comes from electricity sales in local currencies. When local currencies fall against the dollar, as often happens, the burden of those loans grows.

One reason this dynamic has been overlooked is that earlier studies evaluated dams’ economic performance by considering whether international lenders like the World Bank recovered their loans — and in most cases, they did. But the economic impact on host countries was often debilitating. Dam projects are so huge that beginning in the 1980s, dam overruns became major components of debt crises in Turkey, Brazil, Mexico and the former Yugoslavia. “For many countries, the national economy is so fragile that the debt from just one mega-dam can completely negatively affect the national economy,” Mr. Flyvbjerg, the study’s lead investigator, told me.

To underline its point, the study singles out the massive Diamer-Bhasha Dam, now under construction in Pakistan across the Indus River. It is projected to cost $12.7 billion (in 2008 dollars) and finish construction by 2021. But the study suggests that it won’t be completed until 2027, by which time it could cost $35 billion (again, in 2008 dollars) — a quarter of Pakistan’s gross domestic product that year.

Using the study’s criteria, most of the world’s planned mega-dams would be deemed cost-ineffective. That’s unquestionably true of the gargantuan Inga complex of eight dams intended to span the Congo River — its first two projects have produced huge cost overruns — and Brazil’s purported $14 billion Belo Monte Dam, which will replace a swath of Amazonian rain forest with the world’s third-largest hydroelectric dam.

Instead of building enormous, one-of-a-kind edifices like large dams, the study’s authors recommend “agile energy alternatives” like wind, solar and mini-hydropower facilities. “We’re stuck in a 1950s mode where everything was done in a very bespoke, manual way,” Mr. Ansar said over the phone. “We need things that are more easily standardized, things that fit inside a container and can be easily transported.”

All this runs directly contrary to the current international dam-building boom. Chinese, Brazilian and Indian construction companies are building hundreds of dams around the world, and the World Bank announced a year ago that it was reviving a moribund strategy to fund mega-dams. The biggest ones look so seductive, so dazzling, that it has taken us generations to notice: They’re brute-force, Industrial Age artifacts that rarely deliver what they promise.

Issues in Science and TechnologyBook Review: Deep Water

Deep Water by Jacques Leslie. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2005, 352 pp.

Jacques Leslie is a journalist, and Deep Water has a journalist’s style. It reads well and tells a compelling story. The book relates first-person accounts of three protagonists, each of whom is preoccupied with large dam projects. The stories are rich in detail and intended to teach lessons about large projects that are not to be found in the dry reports of development consultants and international organizations.

In the mid-1990s, the World Bank, at the urging of nongovernmental organizations and with the cooperation of donor organizations, supported the development of an independent commission to study the effects of large dams. The World Commission on Dams (WCD) was made up of 10 members with a wide variety of views. The commission’s 400-page report, Dams and Development, appeared in 2000 to great publicity (Nelson Mandela and other dignitaries made speeches at the press conference announcing its release), and the report remains available at the commission’s Web site (dams.org).

In the mid-1990s, the World Bank, at the urging of nongovernmental organizations and with the cooperation of donor organizations, supported the development of an independent commission to study the effects of large dams. The World Commission on Dams (WCD) was made up of 10 members with a wide variety of views. The commission’s 400-page report, Dams and Development, appeared in 2000 to great publicity (Nelson Mandela and other dignitaries made speeches at the press conference announcing its release), and the report remains available at the commission’s Web site (dams.org).

But as Leslie notes, with seeming regret, the report has had little lasting impact on either the World Bank or on the appetite for new dam projects. Many observers think that is all to the good. The dam-building community and many in the development community echo the World Bank’s senior water advisor John Briscoe’s view that the commission’s report was hijacked by dam opponents and does not provide a reasonable path for the future.

Today, 10 years after the hiatus on new dam building that occurred in the mid-1990s, the dam industry is in full gear, especially in South America and Asia, and is also riding a wave of privately financed small and mid-sized projects as a result of rising energy prices. The impact of Dams and Development has turned out to be less than its proponents presumably hoped for. Dam projects remain controversial, but they are moving ahead at a fast rate.

Leslie’s stories show why dam disputes are so contentious, but they offer little help in resolving disputes or setting a workable policy for guiding dam planning. He provides a vivid close-up look at disputes but fails to provide an overview that could help us gain some perspective.

Deep Water follows three of the former WCD commissioners through their daily dealings with dams and other water projects. Leslie chooses one anti-dam activist, one middle-ofthe-road scientist, and one pro-dam water manager. Deep Water is not a book written by someone sitting around a university campus or library, but by someone who spent long stretches of time in the field, on the front lines of the current water wars. Leslie, a former war correspondent, knows his job and does it well.

Medha Patkar is an anti-dam activist in the Narmada River basin of western India, in the states of Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh. Hers is a story that would try the conscience of the most avowed dam proponent. Using Gandhian tactics, she has fought a slowly losing battle with the Indian and state governments over the building of a cascade of dams on the Narmada that was funded in part by the World Bank. She has undertaken fasts, put herself in near-death situations to stop rising water levels, and led dam-site occupations and other nonviolent protests. Although the story of development on the Narmada has many facets, at its core is a story of compassionless dislocations of the local population, incredible mismanagement, and a lack of support for those most affected by the projects. The national and state governments have even ignored resettlement and environmental policies that they were obligated by treaty or law to uphold. As with many large projects, the net economic benefits of the Narmada developments may (or may not) be positive, but the distribution of those benefits is aimed squarely at entrenched economic interests and away from the people displaced, who not surprisingly are poor and relatively powerless. Dam building on the Narmada was in part responsible for the WCD.

Thayer Scudder is a California Institute of Technology anthropologist and expert on resettlement. In contrast to Medha, who is passionately focused on one river basin, Scudder is a scientist who has worked on hundreds of dam projects. Leslie follows Scudder on projects that are mostly in southern Africa (Lesotho, Zimbabwe, and Zambia). Although Scudder is intended to represent a middle-of-the-road perspective, the stories in this second part are anything but. The African projects around which the story is told are disasters. The Kariba project on the Zambezi is a resettlement and ecological nightmare, aided by a good deal of political corruption. Despite this, Scudder is portrayed as retaining his optimism about the potential benefits that can result from well-managed dam projects. Still, by this time in the book, the reader can be forgiven for wondering if there ever is such a thing. We have yet to meet a good dam in Deep Water, though Scudder holds out hope.

Don Blackmore is an Australian water resources manager. His is the story of a “healthy, working river.” To be clear, the Murry River projects in Australia have had adverse effects on the environment and on indigenous peoples. But because there are fewer people affected here than in the other stories, the tales of botched resettlement seem less disturbing. In addition, these projects have benefited from good governance and from the involvement of stakeholders who were richer and more sophisticated than the people fighting the Indian and African projects. The success of water management in New South Wales, Leslie argues, has as much to do with good government as with good dams.

So what does one take away from this lively book? The cover blurbs on Deep Water are misleading. In the end, the book has little, in fact, to do with dams and more to do with public administration and the mismanagement of large infrastructure projects. In reading that dam projects experience delays and cost overruns, usually do not produce the promised economic benefits, and then also cause irreversible environmental harm, I was reminded of Flyybjerg et al.’s recent book on transportation projects (Megaprojects and Risk, Cambridge, 2003). The fundamental issues are the same.

At the heart of the question of all big infrastructure projects is “us.” There are simply too many of us. The debate at the heart of Deep Water is not about dams; it is about the increasing human population and how to sustain it. Human populations need many things to survive. They need potable water, irrigation, power, protection from natural hazards, and many other things that dams provide. Other ways of providing services such as energy (for example, by the use of wood for fuel) also have adverse social and environmental outcomes. The dams debate is still waiting for the impartial analysis promised by the WCD. Deep Water provides fuel for that debate, but little light.

Gregory B. Baecher (gbaecher@umd.edu) is professor of civil and environmental engineering at the University of Maryland.

The story of the Sardar Sarovar Dam (Aired: January 2009)

SARDAR SAROVAR OVERFLOWING…Paresh patel

The World Bank is bringing back big, bad dams

A renewed focus on mega-dams will make matters worse in Africa and benefit companies, not people

Kariba dam, hydroelectric dam on the Zambezi River, Zimbabwe. Photograph: Alamy

The big, bad dams of past decades are back in style.

In the 1950s and ’60s, huge hydropower projects such as the Kariba, Akosombo and Inga dams were supposed to modernise poor African countries almost overnight. It didn’t work out this way. As the independent World Commission on Dams found, such big, complex schemes cost far more but produce less energy than expected. Their primary beneficiaries are mining companies and aluminium smelters, while Africa’s poor have been left high and dry.

The Inga 1 and 2 dams on the Congo River are a case in point. After donors have spent billions of dollars on them, 85% of the electricity in the Democratic Republic of Congo is used by high-voltage consumers but less than 10% of the population has access to electricity. The communities displaced by the Inga and Kariba dams continue to fight for their compensation and economic rehabilitation after 50 years. Instead of offering a shortcut to prosperity, such projects have become an albatross on Africa’s development. Large dams have also helped turn freshwater into the ecosystem most affected by species extinction.

Under public pressure, the World Bank and other financiers largely withdrew from funding large dams in the mid-1990s. For nearly 20 years, the bank has supported mid-sized dams and rehabilitated existing hydropower projects instead.

Following a trend set by new financiers from China and Brazil, the World Bank now wants to return to supporting mega-dams that aim to transform whole regions. In March, it argued that such projects could “catalyse very large-scale benefits to improve access to infrastructure services” and combat climate change at the same time. Its board of directors will discuss the return to mega-dams as part of a new energy strategy on Tuesday.

The World Bank has identified the $12bn (£8bn) Inga 3 Dam on the Congo River – the most expensive hydropower project ever proposed in Africa – and two other multi-billion dollar schemes on the Zambezi River as illustrative examples of its new approach. All three projects would primarily generate electricity for the mining companies and middle-class consumers of Southern Africa.

The World Bank ignores that better solutions are readily available. In the past 10 years, governments and private investors installed more new wind power than hydropower capacity. Last year, even solar power – long decried as a Mickey Mouse technology by the dam industry – caught up with new hydropower investment. Wind and solar power are not only climate friendly, they are also more effective than big dams in reaching the rural poor in sub-Saharan Africa, most of whom are not connected to the electric grid.

The International Energy Agency recommends that more than 60% of the funds required to bring about universal access to electricity be invested in distributed renewable energy projects such as wind, solar and small hydropower plants. Yet so far, funding for bringing these promising technologies to Africa has been woefully lacking. Like other donors, the World Bank is behind the curve on this. In 2007-12, it spent $5.4bn on hydropower, but only $2bn on wind and solar projects combined. A renewed focus on mega-dams would make matters worse.

Is the World Bank blinded by an outdated ideology? More likely, its return to mega-dams is driven by institutional self-interest. A strategy paper leaked from the bank in 2011 recognised that the increase in project size “may seem somewhat at odds with the goal of scaling up activities in areas where many potential projects – such as solar, wind and micro-hydropower … tend to be small”. Yet, the paper argued, the “ratio of preparation and supervision costs to total project size” is bigger for small projects than large, centralised schemes, and so bank managers are “disincentivised” from undertaking small projects.

The World Bank, in other words, still finds it easier to spend billions of dollars on mega-projects than to support the small, decentralized projects that are most effective at expanding energy access in rural areas. It appears to be caught in the development model of past decades. If internal constraints prevent the bank from doing what is best for the poor, governments should find other vehicles for reducing energy poverty and combating climate change.

Viewpoint – The World Bank Versus the World Commission on Dams -click here for PDF

The World Bank is the greatest single source of funds for large dam construction, having provided more than US$50 billion (1992 dollars) for construction of more than 500 large dams in 92 countries. The World Bank has been “directly or indirectly associated” with around 10% of large dams in developing countries (excluding China, where the Bank had funded only eight dams up to 1994). The importance of the World Bank in major dam schemes is illustrated by the fact that it has directly funded four out of the five highest dams in developing countries outside China, three out of the five largest reservoirs in these countries, and three of the five largest hydroplants….